| Advisor |

|

|

|

|

|

||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||

|

|

||||||||||||||||

| Identifying Functions | ||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||

|

|

||||||||||||||||

| Developing Functions | ||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||

|

|

||||||||||||||||

| Guiding Parents | ||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||

|

|

||||||||||||||||

|

T-5: Adequacy of the Cognitive Field (pdf)

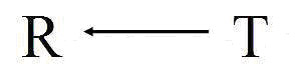

The transformation functions that have been described until now

make an important contribution to knowledge construction by shaping

the initial experience of a problem and by activating and guiding the

learner's reception functions (R-1 to R-10). As thought, cognition

does not begin with reception but with a mental disequilibrium (T-2)

and the early T-functions (T-1 to T-4) that support the formation of

the mental act and guide the collection of information. This can be

depicted as follows:

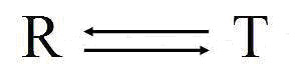

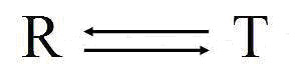

Operating in the perceptual-cognitive interface, the receptive functions convert the objects and events that are registered by the senses into the information that is used for knowledge construction. In quite a literal sense the investment in the receptive functions returns information for use in cognition. The overall relationships can be represented as follows:

The information that is collected is initially placed or buffered in the cognitive field (T-5) where it can be combined with previously collected information and knowledge (T-7 and T-8). By way of analogy the cognitive field can be likened to your computer's RAM. We use the cognitive field when we perform mental tasks. The characteristics of a task determine how narrow or wide the cognitive field needs to be. For example, the multiplication 12.3 x 7.2 requires a wider cognitive field than the multiplication 12 x 7: The reason is that there are more pieces of information in the former task and more steps that have to be accomplished. Just try to do the two tasks in your mind and you will see.

Looking for a notepad or a calculator is usually a good sign that a task is presenting a significant demand on the cognitive field. Saying it is difficult may similarly be a reflection of the nature of the requirement it places on the cognitive field. When doing math, young learners often seek to reduce the pressure on their cognitive field by counting on their fingers but people of all ages embrace devices to reduce the need for a wider cognitive field. For example, we use conversion tables to avoid having to calculate from one unit of measurement to another, from Fahrenheit to Celsius, form hectares to acres. We want robust and easy to use products so we can enjoy their benefits while thinking as little as possible about how they work (cars, appliances).

Students need to develop an understanding of the steps they can take to manage the fit between their cognitive field and the processing demands of the many different tasks they will encounter. That is the focus of this knowledge construction function. Prior to developing this function many students respond to shortfalls in their cognitive field either by letting go of received information or by shutting their input down (R-1). Letting go of information enables them to continue to receive new information. Shutting down input enables them at a minimum to hold on to the information they already have received. Either way, these students are likely to be processing partial and insufficient information when they reason about a task.

Other students who have difficulties with this knowledge construction function may discover that they lose their place in the middle of working on a task. For example, a child gets lost in long division or when taking instructions. Combining multiple sources of information can also be affected by difficulties with the management of the cognitive field leading to successive or alternating ways of dealing with data (R-10). In this process information is easily lost along the way. When this happens many students will attempt to start over a number of times, then raise their hands in frustration and give up.

Managing the adequacy of the cognitive field can be challenging because the need for processing capacity is extremely sensitive to small variations in task characteristics and requirements. A student's cognitive field may be adequate for the multiplication of 9 x 9 but be overtaxed by 9.5 x 9.5. Most people can readily create tasks that render their own cognitive field wholly inadequate. If it isn't accomplished by 9.5 x 9.5 perhaps it would be by 9.12 x 9.83 or a larger number. Verbal challenges are just as easy to create: How many unrelated words (e.g. Elephant, Shoes, Books, Glasses, Airplane, Typewriter, Benadryl, Toothbrush, Blanket, Seatbelt, Milk, Stars) can you listen to at once and then repeat or write out before you run out of space in your cognitive field?

To mediate this function help your students acquire strategies for managing their processing capability. This includes knowing when and how to use note taking, charting and mind mapping strategies to preserve an adequate cognitive field. It includes knowing how to get more out of the existing mental field by organizing information into categories, by using shortcuts, and by creating relationships between discrete pieces of information that may help to structure and hold them together (T-6). For example, it can be much easier to remember an unrelated string of words if relationships are used to connect them as parts of a sequence. Vividly phantasmagorical sequences may be especially effective: An Elephant puts on Shoes, takes his Books, puts on Glasses, boards an Airplane, types on his Typewriter, takes a Benadryl, uses his Toothbrush, asks for a Blanket, checks his Seatbelt, drinks Milk and watches the stars. Try to see how many of these words you remember now.

Shortcuts require knowledge and experience. When available, shortcuts can dramatically cut the demand on the cognitive field. For example to multiply a number ending in .5 by itself, such as 9.5 x 9.5, multiply the nearest lower and the nearest higher integer, 9 and 10, and add 0.25 for a result of 90.25. Check it out and try it with different numbers, e.g. 7.5 x 7.5, 29.5 x 29.5.

Encourage students to explore different modalities for processing information. Some students may process visual information more efficiently than auditory information. Will it help to take mental notes? Will it help to attach concepts? Attaching concepts implies increases in abstractness but we can decrease complexity by increasing abstractness. We give up detail but we work with sets that are easier to manipulate in the mind. Instead of working with banana, trumpet, apple, orange, guitar, tangerine and piano we work with fruits and musical instruments and we could designate X and Y to represent fruits and instruments respectively. We have created a more abstract but less complex way of dealing with information and one that can be managed in a narrower cognitive field.

Operating in the perceptual-cognitive interface, the receptive functions convert the objects and events that are registered by the senses into the information that is used for knowledge construction. In quite a literal sense the investment in the receptive functions returns information for use in cognition. The overall relationships can be represented as follows:

The information that is collected is initially placed or buffered in the cognitive field (T-5) where it can be combined with previously collected information and knowledge (T-7 and T-8). By way of analogy the cognitive field can be likened to your computer's RAM. We use the cognitive field when we perform mental tasks. The characteristics of a task determine how narrow or wide the cognitive field needs to be. For example, the multiplication 12.3 x 7.2 requires a wider cognitive field than the multiplication 12 x 7: The reason is that there are more pieces of information in the former task and more steps that have to be accomplished. Just try to do the two tasks in your mind and you will see.

Looking for a notepad or a calculator is usually a good sign that a task is presenting a significant demand on the cognitive field. Saying it is difficult may similarly be a reflection of the nature of the requirement it places on the cognitive field. When doing math, young learners often seek to reduce the pressure on their cognitive field by counting on their fingers but people of all ages embrace devices to reduce the need for a wider cognitive field. For example, we use conversion tables to avoid having to calculate from one unit of measurement to another, from Fahrenheit to Celsius, form hectares to acres. We want robust and easy to use products so we can enjoy their benefits while thinking as little as possible about how they work (cars, appliances).

Students need to develop an understanding of the steps they can take to manage the fit between their cognitive field and the processing demands of the many different tasks they will encounter. That is the focus of this knowledge construction function. Prior to developing this function many students respond to shortfalls in their cognitive field either by letting go of received information or by shutting their input down (R-1). Letting go of information enables them to continue to receive new information. Shutting down input enables them at a minimum to hold on to the information they already have received. Either way, these students are likely to be processing partial and insufficient information when they reason about a task.

Other students who have difficulties with this knowledge construction function may discover that they lose their place in the middle of working on a task. For example, a child gets lost in long division or when taking instructions. Combining multiple sources of information can also be affected by difficulties with the management of the cognitive field leading to successive or alternating ways of dealing with data (R-10). In this process information is easily lost along the way. When this happens many students will attempt to start over a number of times, then raise their hands in frustration and give up.

Managing the adequacy of the cognitive field can be challenging because the need for processing capacity is extremely sensitive to small variations in task characteristics and requirements. A student's cognitive field may be adequate for the multiplication of 9 x 9 but be overtaxed by 9.5 x 9.5. Most people can readily create tasks that render their own cognitive field wholly inadequate. If it isn't accomplished by 9.5 x 9.5 perhaps it would be by 9.12 x 9.83 or a larger number. Verbal challenges are just as easy to create: How many unrelated words (e.g. Elephant, Shoes, Books, Glasses, Airplane, Typewriter, Benadryl, Toothbrush, Blanket, Seatbelt, Milk, Stars) can you listen to at once and then repeat or write out before you run out of space in your cognitive field?

To mediate this function help your students acquire strategies for managing their processing capability. This includes knowing when and how to use note taking, charting and mind mapping strategies to preserve an adequate cognitive field. It includes knowing how to get more out of the existing mental field by organizing information into categories, by using shortcuts, and by creating relationships between discrete pieces of information that may help to structure and hold them together (T-6). For example, it can be much easier to remember an unrelated string of words if relationships are used to connect them as parts of a sequence. Vividly phantasmagorical sequences may be especially effective: An Elephant puts on Shoes, takes his Books, puts on Glasses, boards an Airplane, types on his Typewriter, takes a Benadryl, uses his Toothbrush, asks for a Blanket, checks his Seatbelt, drinks Milk and watches the stars. Try to see how many of these words you remember now.

Shortcuts require knowledge and experience. When available, shortcuts can dramatically cut the demand on the cognitive field. For example to multiply a number ending in .5 by itself, such as 9.5 x 9.5, multiply the nearest lower and the nearest higher integer, 9 and 10, and add 0.25 for a result of 90.25. Check it out and try it with different numbers, e.g. 7.5 x 7.5, 29.5 x 29.5.

Encourage students to explore different modalities for processing information. Some students may process visual information more efficiently than auditory information. Will it help to take mental notes? Will it help to attach concepts? Attaching concepts implies increases in abstractness but we can decrease complexity by increasing abstractness. We give up detail but we work with sets that are easier to manipulate in the mind. Instead of working with banana, trumpet, apple, orange, guitar, tangerine and piano we work with fruits and musical instruments and we could designate X and Y to represent fruits and instruments respectively. We have created a more abstract but less complex way of dealing with information and one that can be managed in a narrower cognitive field.