| Advisor |

|

|

|

|

|

||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||

|

|

||||||||||||||||

| Identifying Functions | ||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||

|

|

||||||||||||||||

| Developing Functions | ||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||

|

|

||||||||||||||||

| Guiding Parents | ||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||

|

|

||||||||||||||||

|

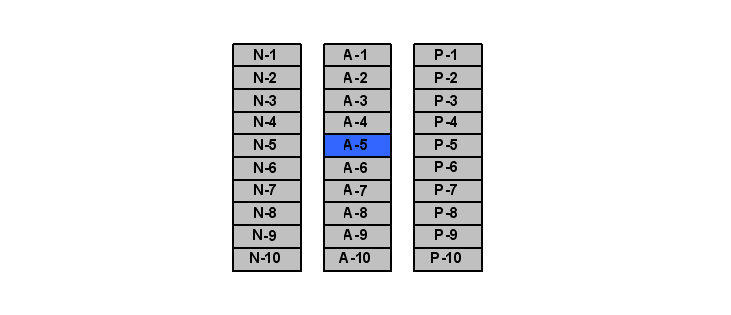

A-5: Academic Standards PDF

The MindLadder model focuses on achieving high academic standards while learning how to learn. There is a content objective (academic standards) and a process objective (learning how to learn). Teachers learn to approach content achievement and the development of learning ability as two mutually reinforcing parts of a single integrated effort with a dual objective.

The dual objective is accomplished by developing students' knowledge construction functions (KCF) within a challenging academic curriculum and an active learning environment. The LearningGuide application maps your students' KCF for you. This enables you to approach the content component of the dual objective from the process side. You can also approach the process component from the content side. This is called backmapping. When you backmap, you decode academic standards to reveal their underlying requirements for KCF. With the MindLadder model, the skill of backmapping is easy to develop and easy to apply across academic standards and curricular objectives covering the elementary, middle, and high school years.

This section of the Advisor enables you to develop the skill of backmapping. Use this skill to identify the knowledge construction functions (KCF) your students need to meet or exceed the high academic standards and curricular objectives which your state or country has set for students at the grade level you teach. Advisor section B-4: Instructional Delivery provides a framework that enables you to become comfortable and skilled with the planning and delivery of lessons that address both content and process objectives for the students in your classroom.

Backmapping Academic Standards PDF

Introduction

The process of identifying knowledge construction functions (KCF) that support an academic standard, or a curricular objective, is identified, for short, as 'backmapping'. Backmapping extracts the process requirements that are needed to achieve the academic content objectives. Academic standards provide inherently relevant and also convenient practice materials for backmapping.

When students fail to progress in the academic subject areas, the educational response is often to teach the content once again even if re-teaching already has been tried in vain. Backmapping enables you to discover the functional prerequisites students must have to operate successfully on the content embedded within a standard. Backmapping followed by the development of the requisite KCF provides a constructive learning centered alternative to re-teaching.

Once you have acquired familiarity with backmapping, you can use it to elucidate the KCF or process learning needs behind any academic standard or curricular objective. This is a useful skill when you plan and deliver your lessons.

You can also create classroom learning activities that focus directly on the process of backmapping itself. In such activities, you and your students can identify the underlying process requirements of upcoming academic standards. The activity becomes a way of preparing to tackle forthcoming subject area goals. Backmapped KCF identified by students in pairs or small groups can be vetted in a whole group discussion. Backmapped standards are likely to be perceived as more readily achievable by your students - even more so if they know they can anticipate an opportunity to develop the prerequisite KCF in your classroom. Confidence and expectations of success may increase even among students with an established history of learning difficulties and school failure.

The materials in this section of the LearningGuide Advisor enable you to develop the skill of backmapping. Backmapping can be illustrated by any set of standards. While children develop more abstract levels of reasoning as they go through the elementary, middle, and high school years, the process of backmapping does not vary across grade levels. With this in mind, ten middle school standards were selected from a set of standards developed by the State of Georgia.

Study the 10 examples. Then try out your new backmapping skills on the standards, or curricular objectives, you use for the specific subject areas and grade levels you teach. Remember, it is often possible to construe a task so many KCF will come to the fore. Try to identify just the key functions.

The examples are listed below by grade level and subject area. Some are fairly complex; some are fairly simple. A hotlink provides direct access to each entry. The same layout is used to analyze all the examples, but detailed explanations accompany the first ones while terser summaries are provided for the later ones. Use the thorough explanations to study the reasoning that supports the process of backmapping. Use the sketchy ones to get acquainted with a summary format that may be convenient also for you to use as you gain familiarity with the MindLadder functions and backmapping. For purposes of illustration, some of the later examples provide a more exhaustive list of functions. However, remember that you generally will focus on just one or two KCF when you prepare and deliver any given lesson (see B-5: Instructional Delivery: Connecting Content and Process).

Below is the common layout for the 10 examples:

The language of the standard is provided along with the number indicating its serial position within the set of standards from which it was drawn. This is followed by a list of key KCF that are needed to operate cognitively upon the standard. The list is not necessarily exhaustive, and you may be able to identify additional KCF that merit attention. To some degree, the listed functions also reflect the benefit of selecting different functions across the ten examples. In other words, functions that were explained in earlier examples were given less attention in later examples (even if relevant) so other functions might be highlighted as well.

The list is followed by an explanation of the connection between the identified KCF and the standard. This explanation will often include references to secondary functions that didn't make the top list. - Note that Advisor section B-5: General Strategies provides more information about each function and how you can develop it in the classroom.

Following the explanation, a summary presents the key KCF in the graph format used throughout the LearningGuide. The illustrated standard provides the caption. Use this resource for a quick review and snapshot of how the standard is backmapped.

The MindLadder model focuses on achieving high academic standards while learning how to learn. There is a content objective (academic standards) and a process objective (learning how to learn). Teachers learn to approach content achievement and the development of learning ability as two mutually reinforcing parts of a single integrated effort with a dual objective.

The dual objective is accomplished by developing students' knowledge construction functions (KCF) within a challenging academic curriculum and an active learning environment. The LearningGuide application maps your students' KCF for you. This enables you to approach the content component of the dual objective from the process side. You can also approach the process component from the content side. This is called backmapping. When you backmap, you decode academic standards to reveal their underlying requirements for KCF. With the MindLadder model, the skill of backmapping is easy to develop and easy to apply across academic standards and curricular objectives covering the elementary, middle, and high school years.

This section of the Advisor enables you to develop the skill of backmapping. Use this skill to identify the knowledge construction functions (KCF) your students need to meet or exceed the high academic standards and curricular objectives which your state or country has set for students at the grade level you teach. Advisor section B-4: Instructional Delivery provides a framework that enables you to become comfortable and skilled with the planning and delivery of lessons that address both content and process objectives for the students in your classroom.

Backmapping Academic Standards PDF

Introduction

The process of identifying knowledge construction functions (KCF) that support an academic standard, or a curricular objective, is identified, for short, as 'backmapping'. Backmapping extracts the process requirements that are needed to achieve the academic content objectives. Academic standards provide inherently relevant and also convenient practice materials for backmapping.

When students fail to progress in the academic subject areas, the educational response is often to teach the content once again even if re-teaching already has been tried in vain. Backmapping enables you to discover the functional prerequisites students must have to operate successfully on the content embedded within a standard. Backmapping followed by the development of the requisite KCF provides a constructive learning centered alternative to re-teaching.

Once you have acquired familiarity with backmapping, you can use it to elucidate the KCF or process learning needs behind any academic standard or curricular objective. This is a useful skill when you plan and deliver your lessons.

You can also create classroom learning activities that focus directly on the process of backmapping itself. In such activities, you and your students can identify the underlying process requirements of upcoming academic standards. The activity becomes a way of preparing to tackle forthcoming subject area goals. Backmapped KCF identified by students in pairs or small groups can be vetted in a whole group discussion. Backmapped standards are likely to be perceived as more readily achievable by your students - even more so if they know they can anticipate an opportunity to develop the prerequisite KCF in your classroom. Confidence and expectations of success may increase even among students with an established history of learning difficulties and school failure.

The materials in this section of the LearningGuide Advisor enable you to develop the skill of backmapping. Backmapping can be illustrated by any set of standards. While children develop more abstract levels of reasoning as they go through the elementary, middle, and high school years, the process of backmapping does not vary across grade levels. With this in mind, ten middle school standards were selected from a set of standards developed by the State of Georgia.

Study the 10 examples. Then try out your new backmapping skills on the standards, or curricular objectives, you use for the specific subject areas and grade levels you teach. Remember, it is often possible to construe a task so many KCF will come to the fore. Try to identify just the key functions.

The examples are listed below by grade level and subject area. Some are fairly complex; some are fairly simple. A hotlink provides direct access to each entry. The same layout is used to analyze all the examples, but detailed explanations accompany the first ones while terser summaries are provided for the later ones. Use the thorough explanations to study the reasoning that supports the process of backmapping. Use the sketchy ones to get acquainted with a summary format that may be convenient also for you to use as you gain familiarity with the MindLadder functions and backmapping. For purposes of illustration, some of the later examples provide a more exhaustive list of functions. However, remember that you generally will focus on just one or two KCF when you prepare and deliver any given lesson (see B-5: Instructional Delivery: Connecting Content and Process).

Below is the common layout for the 10 examples:

The language of the standard is provided along with the number indicating its serial position within the set of standards from which it was drawn. This is followed by a list of key KCF that are needed to operate cognitively upon the standard. The list is not necessarily exhaustive, and you may be able to identify additional KCF that merit attention. To some degree, the listed functions also reflect the benefit of selecting different functions across the ten examples. In other words, functions that were explained in earlier examples were given less attention in later examples (even if relevant) so other functions might be highlighted as well.

The list is followed by an explanation of the connection between the identified KCF and the standard. This explanation will often include references to secondary functions that didn't make the top list. - Note that Advisor section B-5: General Strategies provides more information about each function and how you can develop it in the classroom.

Following the explanation, a summary presents the key KCF in the graph format used throughout the LearningGuide. The illustrated standard provides the caption. Use this resource for a quick review and snapshot of how the standard is backmapped.

Backmapping Academic Standards: Example #1 PDF

Grade 6 - Social Studies

Standard #15: Summarizes important political developments of the Americas, Europe, and Oceania, and explains the spatial divisions of these regions and how cooperation and conflict contribute to the development of these divisions.

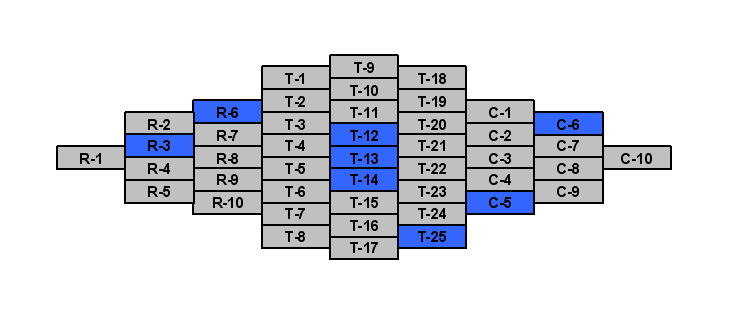

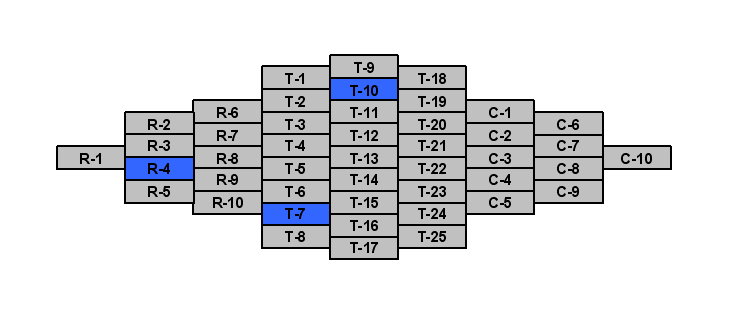

The key verbs in this standard are: summarizes and explains. 'Summarizes' entails the KCF of T-25: Summative Thinking. This function is used to aggregate information, search for cause-effect relationships, discover recurrences and regularities, identify antecedents and consequents, formulate rules and assess their stability. Summative thinking provides a foundation for predicting and forecasting. In the absence of this KCF the learner's experience consists of isolated episodes that remain disconnected and disassociated from one another. T-14: Need to Search for and Establish Relationships (see below) is a prerequisite for summative thinking.

'Explains' draws on the KCF of C-5: Countering Egocentric Style and C-6: Verbal Tools and Concepts. They orient the learner to adjust communication with reference to the knowledge and viewpoint of others and to avoid ambiguity where closer approximation and precision are possible. The learner provides assumptions and supporting arguments to enable others to understand the learner's perspective. In the absence of these KCF, learners communicate in a self-centered, imprecise and vague manner that may obscure even well-developed responses.

Let's take a look now at nouns and adjectives. Let's start with spatial. 'Spatial' implicates the KCF of R-3: Spatial Orientation. Together with R-4: Temporal Orientation, spatial orientation lends a critical measure of stability to a learner's cognition and information processing. This can affect both the personal system of reference (left, right, front, back), which is centered within the individual, and systems that are independent off the individual's orientation (e.g. North, South, East, West). In the absence of this KCF learners are easily confused and disoriented by spatial references. Information seems to slip and slide, and it is difficult for the learner to form and maintain stable mental representations (T-7: Mental Representations). Frustration and task rejection may ensue.

'Developments' implies the KCF of T-12: Generation of Mental Transformations. Mental transformations take their point of departure in mental representations. The successful use of this KCF, therefore, is related both to T-7: Mental Representation and R-3: Spatial Orientation. T-12 enables the learner to experience change as a series of states, where one state changes into another that in turn may change into yet another, and so forth, as a sequence of gradual, evolutionary developments. The ability to apply this KCF plays a critical role in the perception of continuity and change over time. In its absence, change is experienced not as a gradual process but as abrupt and discontinuous.

The geographical names (America, Europe, and Oceania) and the nouns regions, division, political, cooperation and conflict implicate the KCF of R-6: Verbal Tools and Concepts. Teachers must provide verbal tools and concepts as needed and must facilitate their students' discovery and understanding of their use. However, students with this KCF know that any subject area will have verbal tools and concepts that must be registered and understood in order to operate effectively within it. The absence of this KCF limits the quantity of information the learner can gather and the distinctions the learner is able to make.

Perhaps the most central process requirement of this standard is the need to search for and establish relationships (T-14). This function drives the search for connections among the individual components of a problem, and it underlies the use of both hypothetical (T-11) and inferential thinking (T-16). This KCF, likewise, supports the application of lattice-type thinking (T-15) which is used to search for relationships between relationships. For example, in the given standard, the concept of resources is needed to link the concepts of cooperation and conflict. - In the absence of T-14: Need to Search for and Establish Relationships learners tend to allocate inadequate levels of mental resources to the tasks they confront. Rather than investing energy and effort, such learners respond with passivity in the face of the need to construct knowledge. The result is shallow reasoning where relationships are not established, not tested, and not used to build upon, even when the learner may be capable of doing so.

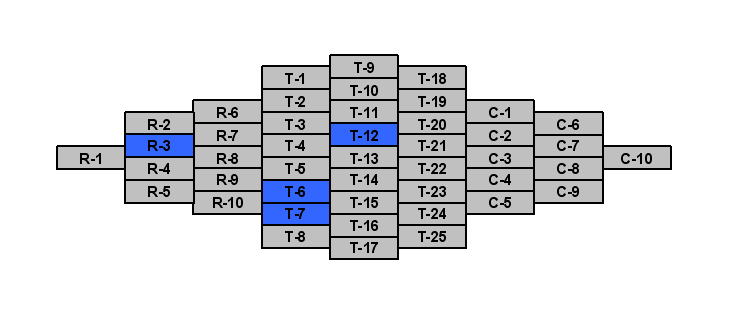

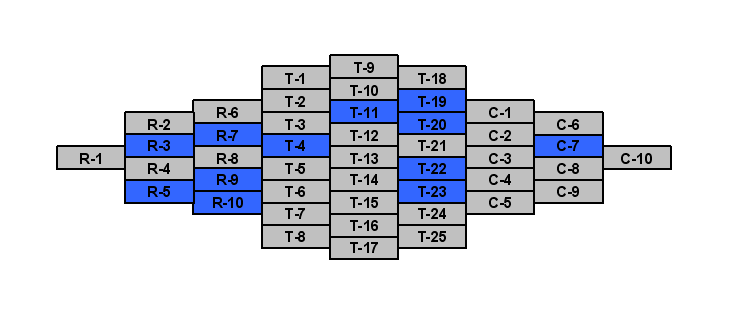

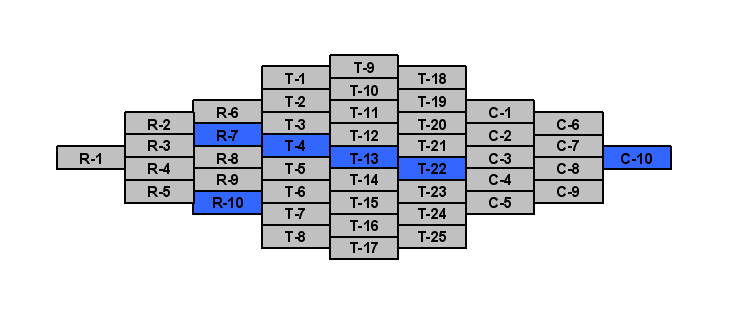

Backmapping Example #1: Grade 6 - Social Studies

Standard: Summarizes important political developments of the Americas, Europe, and Oceania, and explains the spatial divisions of these regions and how cooperation and conflict contribute to the development of these divisions.

Grade 6 - Social Studies

Standard #15: Summarizes important political developments of the Americas, Europe, and Oceania, and explains the spatial divisions of these regions and how cooperation and conflict contribute to the development of these divisions.

- R-3: Spatial Orientation

- R-6: Verbal Tools and Concepts (Reception)

- T-12: Generation of Mental Transformations

- T-13: Abstractions

- T-14: Need to Search for and Establish Relationships

- T-25: Summative Thinking

- C-5: Countering Egocentric Style

- C-6: Verbal Tools and Concepts (Communication)

The key verbs in this standard are: summarizes and explains. 'Summarizes' entails the KCF of T-25: Summative Thinking. This function is used to aggregate information, search for cause-effect relationships, discover recurrences and regularities, identify antecedents and consequents, formulate rules and assess their stability. Summative thinking provides a foundation for predicting and forecasting. In the absence of this KCF the learner's experience consists of isolated episodes that remain disconnected and disassociated from one another. T-14: Need to Search for and Establish Relationships (see below) is a prerequisite for summative thinking.

'Explains' draws on the KCF of C-5: Countering Egocentric Style and C-6: Verbal Tools and Concepts. They orient the learner to adjust communication with reference to the knowledge and viewpoint of others and to avoid ambiguity where closer approximation and precision are possible. The learner provides assumptions and supporting arguments to enable others to understand the learner's perspective. In the absence of these KCF, learners communicate in a self-centered, imprecise and vague manner that may obscure even well-developed responses.

Let's take a look now at nouns and adjectives. Let's start with spatial. 'Spatial' implicates the KCF of R-3: Spatial Orientation. Together with R-4: Temporal Orientation, spatial orientation lends a critical measure of stability to a learner's cognition and information processing. This can affect both the personal system of reference (left, right, front, back), which is centered within the individual, and systems that are independent off the individual's orientation (e.g. North, South, East, West). In the absence of this KCF learners are easily confused and disoriented by spatial references. Information seems to slip and slide, and it is difficult for the learner to form and maintain stable mental representations (T-7: Mental Representations). Frustration and task rejection may ensue.

'Developments' implies the KCF of T-12: Generation of Mental Transformations. Mental transformations take their point of departure in mental representations. The successful use of this KCF, therefore, is related both to T-7: Mental Representation and R-3: Spatial Orientation. T-12 enables the learner to experience change as a series of states, where one state changes into another that in turn may change into yet another, and so forth, as a sequence of gradual, evolutionary developments. The ability to apply this KCF plays a critical role in the perception of continuity and change over time. In its absence, change is experienced not as a gradual process but as abrupt and discontinuous.

The geographical names (America, Europe, and Oceania) and the nouns regions, division, political, cooperation and conflict implicate the KCF of R-6: Verbal Tools and Concepts. Teachers must provide verbal tools and concepts as needed and must facilitate their students' discovery and understanding of their use. However, students with this KCF know that any subject area will have verbal tools and concepts that must be registered and understood in order to operate effectively within it. The absence of this KCF limits the quantity of information the learner can gather and the distinctions the learner is able to make.

Perhaps the most central process requirement of this standard is the need to search for and establish relationships (T-14). This function drives the search for connections among the individual components of a problem, and it underlies the use of both hypothetical (T-11) and inferential thinking (T-16). This KCF, likewise, supports the application of lattice-type thinking (T-15) which is used to search for relationships between relationships. For example, in the given standard, the concept of resources is needed to link the concepts of cooperation and conflict. - In the absence of T-14: Need to Search for and Establish Relationships learners tend to allocate inadequate levels of mental resources to the tasks they confront. Rather than investing energy and effort, such learners respond with passivity in the face of the need to construct knowledge. The result is shallow reasoning where relationships are not established, not tested, and not used to build upon, even when the learner may be capable of doing so.

Backmapping Example #1: Grade 6 - Social Studies

Standard: Summarizes important political developments of the Americas, Europe, and Oceania, and explains the spatial divisions of these regions and how cooperation and conflict contribute to the development of these divisions.

Backmapping Academic Standards: Example #2 PDF

Grade 8 - Social Studies

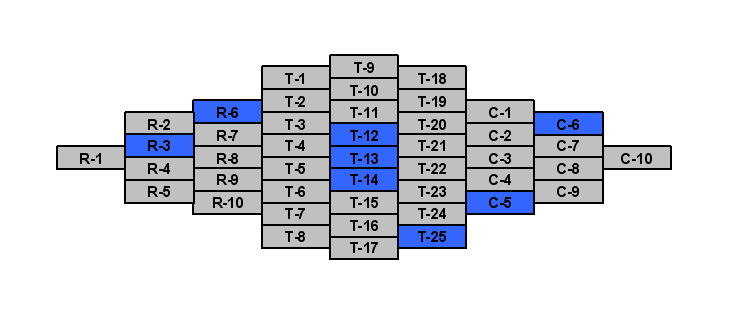

Standard 72: Places related events in chronological order.

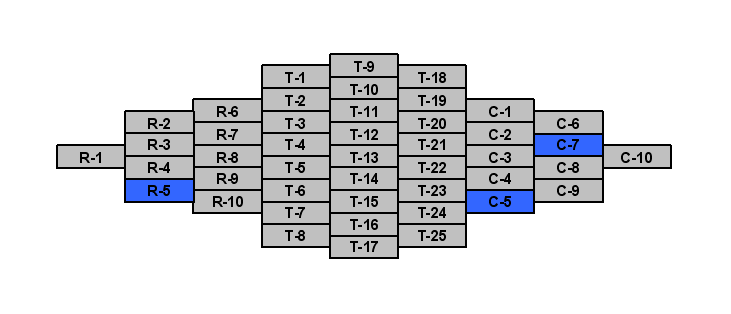

A simple task becomes an indecipherable problem in the absence of the prerequisite KCF. This is illustrated by the familiar social studies standard in this example. Let's take a look at each of the three functions in turn and then discuss how each supports the others in the performance of the required task.

Temporal orientation (R-4) is necessary for a learner to relate to objects or events that are not available to the senses in the present moment. The concepts of past and future rely on temporal orientation (see also below), as do the range of ways to experience the occurrence of events relative to one another in time, such as before, after, earlier than, later than, sooner than, faster than, first, second, last and so on. Without this KCF, students are easily confused by tasks that involve temporal relationships.

While other KCF such as adequacy of the cognitive field (T-5) and evoking from memory (T-8) also can play a role, the inability to structure one's experiences with stable temporal referents creates disarray among them. Together with spatial orientation (R-3), temporal orientation (R-4) secures the stability of the cognitive foundations of the learner's experience. Other KCF build on these foundations. First, and chief, among these is the formation of mental representations (T-7).

The KCF of mental representations (T-7) enables the learner to form ideas. It combines newly collected information with information stored as knowledge and experience in memory. Mental representation is needed for any form of cognitive functioning that goes beyond reproductive or imitative behavior. In the absence of this KCF, the learner must rely on concrete, trial-and-error modes of functioning in place of more efficient, representational modes of functioning.

Mental representation (T-7) is a prerequisite for abstract levels of functioning including hypothetical thinking (T-11), mental transformations (T-12) and the application of strategies for inferential thinking (T-16). Together with temporal orientation (R-4), mental representation (T-7) is a prerequisite for projecting into the past and future, and it interfaces with such KCF as goal-seeking and goal setting (T-22), planning (T-23) and goal achievement (T-24). It is a prerequisite, too, for ordering events (T-10) that are not available in a concrete, perceptual format, as is typically the case, as in this standard, when students have to rely on their knowledge and memory to place historical events in chronological order.

Once entities are available as mental representations, the KCF of ordering and grouping (T-10) enables the learner to organize them into categories and place them into sequences. In the case of the standard we are backmapping here, this KCF is needed first to group related events and then to sequence them chronologically. Ordering and grouping (T-10) enable students to organize unstructured information into more coherent sets of data. In the absence of this KCF, learners are unable to consider discrete objects or events under the umbrella of shared attributes or commonalities. As a result, the students are unable to form the more abstract groupings that are used in many higher levels of cognitive processing. - Operating upon grouped data is a prerequisite for some forms of logical reasoning including syllogistic thinking (T-16: Strategies for Inferential Thinking).

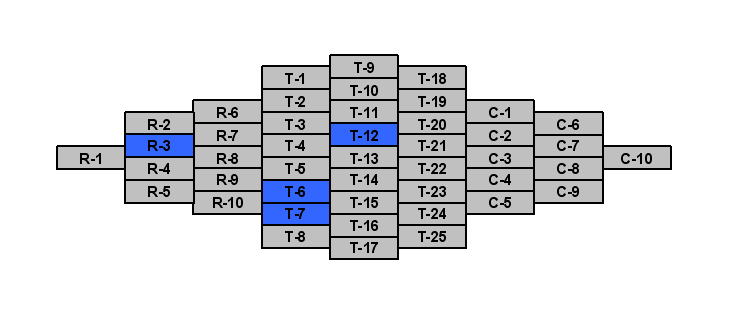

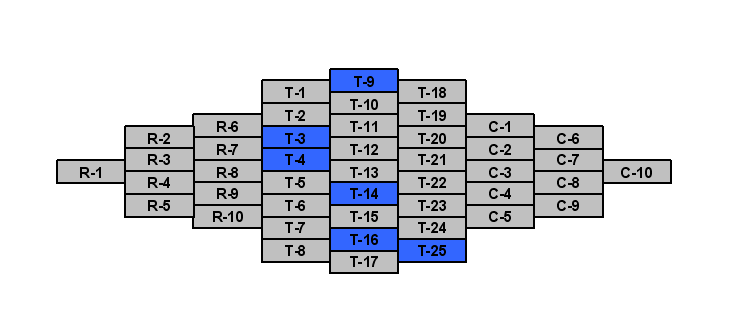

Backmapping Example #2: Grade 8 - Social Studies

Standard: Places related events in chronological order.

Grade 8 - Social Studies

Standard 72: Places related events in chronological order.

A simple task becomes an indecipherable problem in the absence of the prerequisite KCF. This is illustrated by the familiar social studies standard in this example. Let's take a look at each of the three functions in turn and then discuss how each supports the others in the performance of the required task.

Temporal orientation (R-4) is necessary for a learner to relate to objects or events that are not available to the senses in the present moment. The concepts of past and future rely on temporal orientation (see also below), as do the range of ways to experience the occurrence of events relative to one another in time, such as before, after, earlier than, later than, sooner than, faster than, first, second, last and so on. Without this KCF, students are easily confused by tasks that involve temporal relationships.

While other KCF such as adequacy of the cognitive field (T-5) and evoking from memory (T-8) also can play a role, the inability to structure one's experiences with stable temporal referents creates disarray among them. Together with spatial orientation (R-3), temporal orientation (R-4) secures the stability of the cognitive foundations of the learner's experience. Other KCF build on these foundations. First, and chief, among these is the formation of mental representations (T-7).

The KCF of mental representations (T-7) enables the learner to form ideas. It combines newly collected information with information stored as knowledge and experience in memory. Mental representation is needed for any form of cognitive functioning that goes beyond reproductive or imitative behavior. In the absence of this KCF, the learner must rely on concrete, trial-and-error modes of functioning in place of more efficient, representational modes of functioning.

Mental representation (T-7) is a prerequisite for abstract levels of functioning including hypothetical thinking (T-11), mental transformations (T-12) and the application of strategies for inferential thinking (T-16). Together with temporal orientation (R-4), mental representation (T-7) is a prerequisite for projecting into the past and future, and it interfaces with such KCF as goal-seeking and goal setting (T-22), planning (T-23) and goal achievement (T-24). It is a prerequisite, too, for ordering events (T-10) that are not available in a concrete, perceptual format, as is typically the case, as in this standard, when students have to rely on their knowledge and memory to place historical events in chronological order.

Once entities are available as mental representations, the KCF of ordering and grouping (T-10) enables the learner to organize them into categories and place them into sequences. In the case of the standard we are backmapping here, this KCF is needed first to group related events and then to sequence them chronologically. Ordering and grouping (T-10) enable students to organize unstructured information into more coherent sets of data. In the absence of this KCF, learners are unable to consider discrete objects or events under the umbrella of shared attributes or commonalities. As a result, the students are unable to form the more abstract groupings that are used in many higher levels of cognitive processing. - Operating upon grouped data is a prerequisite for some forms of logical reasoning including syllogistic thinking (T-16: Strategies for Inferential Thinking).

Backmapping Example #2: Grade 8 - Social Studies

Standard: Places related events in chronological order.

Backmapping Academic Standards: Example #3 PDF

Grade 7 - Language Arts

Standard 10: Applies standard rules of punctuation.

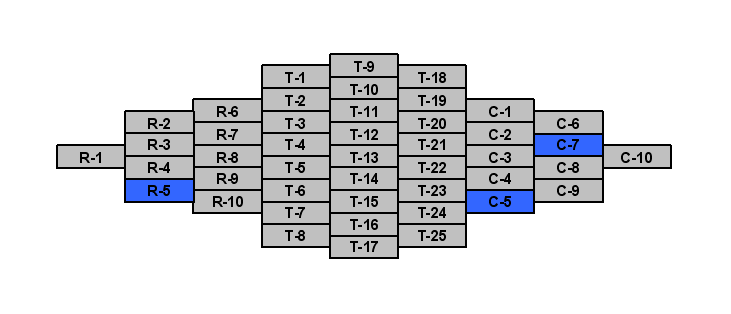

First off, to apply standard rules of punctuation students have to know a set of signs that is used to encode or express the rules {(. , ; ? ! : ")}. The signs must be taught, whether by instruction or through self-study, since they are arbitrary and the products of convention. For example, students must be taught that '.' and ',' both mean a pause and that the pause indicated by '.' is longer than the one indicated by ','.

Understanding and using signs requires a KCF that enables substitutes to be used in place of objects or event (R-5). In other words, signs such as '.' or ',' must be seen to stand for or to represent something else. Signs are substitutes. They are surrogates or proxies that, in this case, point, respectively, to a long and a short pause in the reading of text.

Signs represent one of three kinds of substitutes. The other two are traces and symbols. The three types of substitutes are the building blocks of knowledge construction. Over the ages, people have used them to create the abundance of cultures, domains of knowledge and modalities of expression in language and art that are seen in the world.

Traces, symbols and signs are all substitutes; they all point to something else. For example, a footprint in the sand (a trace) points to the being that placed it there. A national anthem (a symbol) points to the country for which it is sung. The letters A-T-C (three signs), when ordered correctly, stands for a common house pet.

The difference between traces, symbols and signs is in their degree of overlap or 'participation' with the object or event they substitute for. Advisor section B-3 provides a classroom dialogue that illustrates how this KCF can be introduced in the classroom. It focuses on traces and signs. Let's take a closer look here at the concept of participation across all three types of substitutes.

Traces participate most directly in what they point to. They are left behind. For example, a soundtrack on a music CD is a trace of the recording artist. We listen to the trace of the artist but say we listen to the artist. The trace was created or left behind as a substitute for the artist. A dinosaur skeleton is a trace of the animal that once lived. We look at a photographic imprint of a long-deceased family member and say "this is my great-grandmother" although the photograph is only a trace of the person who once lived.

Like traces, symbols participate in what they point to, but, unlike traces, symbols are formed by a cultural process that gives rise to their meaning within groups of people that ascribe significance to them. Symbols can loose or change their meaning but many are widely recognized and durable over time. The Red Cross is renowned as a symbol of aid to cope with emergencies. The right-facing swastika adopted as a Nazi symbol has remained odious and contemptible in Western cultures since WWII. National flags symbolize the countries for which they are flown. Although the announcer at the Parade of Nations at the Olympic Games proclaims 'Next, the United States!' all you see is an athlete holding aloft a piece of cloth with stars and stripes on a pole. The feeling of pride and the heave in your chest that comes when your nation's flag is carried into the stadium are indications of the symbolic status of your nation's flag.

Unlike traces and symbols, signs participate in what they point to only by convention. It is important to remember that punctuation rules, being signs, represent conventions that evolve over time and vary across national boundaries where the same language is spoken (e.g. punctuation rules for English in Great Britain and the United States). Traffic signs, likewise, are adopted by convention. Letters are combined into words that, similarly, are given meaning by convention. Mathematical signs denote specific operations that also are assigned by convention. For example '=' usually means equal to, '+' means addition and so on.

Now we can see that the application of standard rules of punctuation, as embodied in the academic objective in this example, requires the KCF of R-5: Traces, Symbols and Signs. In the absence of this function students interpret signs concretely and do not see them as standing for or pointing to something else. For example, '=' is just two horizontal and '+" two crossed lines. Following traumatic brain injury, it is not uncommon to observe what may be only a temporary impairment of this KCF where people interpret symbols and signs concretely. A white dove is just that, a white dove; it doesn't signify peace. The etching in the tree is just a heart and an arrow, not a symbol of love.

The application of standard rules of punctuation is supported by the KCF of C-5: Countering Egocentric Style and C-7: Effort (Precision, Persistence and Accuracy). A prepared text easily acquires a self-centered and slipshod appearance in the absence of these functions. Rules of punctuation are designed to reduce ambiguity in a sentence and induce a supportive, comfortable pace of reading. The writer accomplishes these objectives by stepping outside the egocentric self to examine the language and look for ambiguities of meaning that can be eliminated by punctuation. The process may require a deliberate allocation of effort (C-7) to ensure that the use of punctuation is supported by adequate levels of precision, persistence and accuracy.

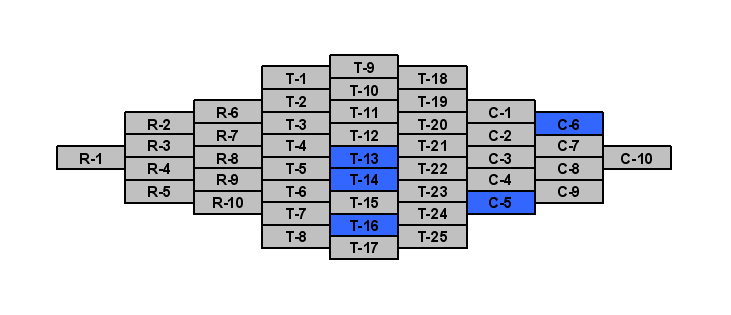

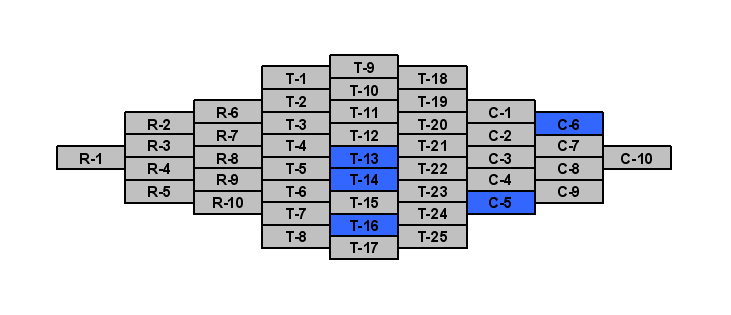

Backmapping Example #3: Grade 7 - Language Arts

Standard: Applies standard rules of punctuation.

Grade 7 - Language Arts

Standard 10: Applies standard rules of punctuation.

- R-5: Traces, Symbols and Signs

- C-5: Countering Egocentric Style

- C-7: Effort (Precision, Persistence and Accuracy)

First off, to apply standard rules of punctuation students have to know a set of signs that is used to encode or express the rules {(. , ; ? ! : ")}. The signs must be taught, whether by instruction or through self-study, since they are arbitrary and the products of convention. For example, students must be taught that '.' and ',' both mean a pause and that the pause indicated by '.' is longer than the one indicated by ','.

Understanding and using signs requires a KCF that enables substitutes to be used in place of objects or event (R-5). In other words, signs such as '.' or ',' must be seen to stand for or to represent something else. Signs are substitutes. They are surrogates or proxies that, in this case, point, respectively, to a long and a short pause in the reading of text.

Signs represent one of three kinds of substitutes. The other two are traces and symbols. The three types of substitutes are the building blocks of knowledge construction. Over the ages, people have used them to create the abundance of cultures, domains of knowledge and modalities of expression in language and art that are seen in the world.

Traces, symbols and signs are all substitutes; they all point to something else. For example, a footprint in the sand (a trace) points to the being that placed it there. A national anthem (a symbol) points to the country for which it is sung. The letters A-T-C (three signs), when ordered correctly, stands for a common house pet.

The difference between traces, symbols and signs is in their degree of overlap or 'participation' with the object or event they substitute for. Advisor section B-3 provides a classroom dialogue that illustrates how this KCF can be introduced in the classroom. It focuses on traces and signs. Let's take a closer look here at the concept of participation across all three types of substitutes.

Traces participate most directly in what they point to. They are left behind. For example, a soundtrack on a music CD is a trace of the recording artist. We listen to the trace of the artist but say we listen to the artist. The trace was created or left behind as a substitute for the artist. A dinosaur skeleton is a trace of the animal that once lived. We look at a photographic imprint of a long-deceased family member and say "this is my great-grandmother" although the photograph is only a trace of the person who once lived.

Like traces, symbols participate in what they point to, but, unlike traces, symbols are formed by a cultural process that gives rise to their meaning within groups of people that ascribe significance to them. Symbols can loose or change their meaning but many are widely recognized and durable over time. The Red Cross is renowned as a symbol of aid to cope with emergencies. The right-facing swastika adopted as a Nazi symbol has remained odious and contemptible in Western cultures since WWII. National flags symbolize the countries for which they are flown. Although the announcer at the Parade of Nations at the Olympic Games proclaims 'Next, the United States!' all you see is an athlete holding aloft a piece of cloth with stars and stripes on a pole. The feeling of pride and the heave in your chest that comes when your nation's flag is carried into the stadium are indications of the symbolic status of your nation's flag.

Unlike traces and symbols, signs participate in what they point to only by convention. It is important to remember that punctuation rules, being signs, represent conventions that evolve over time and vary across national boundaries where the same language is spoken (e.g. punctuation rules for English in Great Britain and the United States). Traffic signs, likewise, are adopted by convention. Letters are combined into words that, similarly, are given meaning by convention. Mathematical signs denote specific operations that also are assigned by convention. For example '=' usually means equal to, '+' means addition and so on.

Now we can see that the application of standard rules of punctuation, as embodied in the academic objective in this example, requires the KCF of R-5: Traces, Symbols and Signs. In the absence of this function students interpret signs concretely and do not see them as standing for or pointing to something else. For example, '=' is just two horizontal and '+" two crossed lines. Following traumatic brain injury, it is not uncommon to observe what may be only a temporary impairment of this KCF where people interpret symbols and signs concretely. A white dove is just that, a white dove; it doesn't signify peace. The etching in the tree is just a heart and an arrow, not a symbol of love.

The application of standard rules of punctuation is supported by the KCF of C-5: Countering Egocentric Style and C-7: Effort (Precision, Persistence and Accuracy). A prepared text easily acquires a self-centered and slipshod appearance in the absence of these functions. Rules of punctuation are designed to reduce ambiguity in a sentence and induce a supportive, comfortable pace of reading. The writer accomplishes these objectives by stepping outside the egocentric self to examine the language and look for ambiguities of meaning that can be eliminated by punctuation. The process may require a deliberate allocation of effort (C-7) to ensure that the use of punctuation is supported by adequate levels of precision, persistence and accuracy.

Backmapping Example #3: Grade 7 - Language Arts

Standard: Applies standard rules of punctuation.

Backmapping Academic Standards: Example #4 PDF

Grade 8 - Language Arts

Standard 14: Follows oral directions and asks questions for clarification.

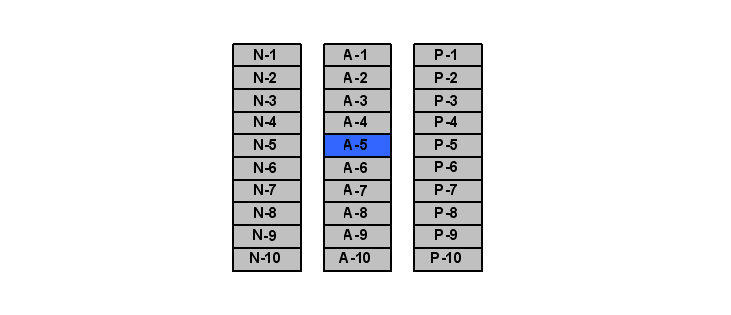

In order to follow oral directions, students must attend to the incoming information without being distracted by external or internal sources of interference. This implicates the KCF of R-2: Attention. The brain registers large amounts of information at any moment, but we only attend to a tiny subset. Within limits, as is the case with all the KCF, we have the ability to regulate how we allocate our attention. We can choose to listen, and noises we until then ignored pop out from the background. We can choose to be on the lookout for visual details, as when a detective scrutinizes a video that captured a crime scene. The development of attention as a KCF equips learners with the ability to regulate attention as a matter of a conscious choice. Students learn the relationship between allocating attention and gathering information. In the absence of this function, students may drift and be easy pray for distractions and even small variations in motivation.

The development of verbal tools and concepts (R-6) equips students with an understanding of the need for such tools within any area of academic functioning. Once they have this KCF, students will anticipate that verbal tools and concepts will accompany any new task and subject area, and they will be on the lookout for them. Students will know that these devices for information processing must be acquired in one or more of a small number of ways: Either they mush be taught by the teacher, looked up in a dictionary, inferred by context or acquired from questioning. When a learner encounters words or concepts that are ambiguous or unknown, it is this KCF which orients the student to take appropriate steps to achieve the necessary clarification. In the absence of this function, students tend to skip over new words and concepts with the predictable impact on the quality of their knowledge construction and performance.

Except when brief instructions are heard and carried out, students need first to store oral directions in memory and, then, at some later point, evoke them as needed. Both T-6: Interiorization and T-7: Mental Representation are involved in storing information in memory. Here, however, our focus is not on the self-evident problem that information not stored in memory cannot be recalled. Our focus, rather, is on the retrieval of stored information.

We can distinguish between two types of memory: Associative and analytical. The associative type is experienced as largely involuntary. It generally dominates the experience of memory as images enter the mind seemingly on their own accord. Our interest is in the analytical type which is activated by a KCF that orients the learner to deliberately search memory in order to retrieve stored information (T-8: Evoking from Memory). Unlike associative memory, evoking from memory is the product of a volitional act. In the absence of this KCF, students manifest a passive attitude towards memory that enables even properly stored information to go unclaimed when needed. The relative unfamiliarity with this KCF makes educators prone to conclude that students don't know when they, in fact, don't remember.

Here is the standard once again: Follows oral directions and asks questions for clarification. Let's turn to the portion about asking questions for clarification. The wording 'for clarification' hints at the difference between those who ask questions to advance the process of knowledge construction versus those who ask questions to bypass it ("What's the answer?") Poorly developed knowledge construction functions are often associated with unrewarded effort and low expectations of success. In traditional classrooms students with poor KCF frequently want just to be done and move on ("Hey, man, can't you just give me the answer?") Well developed KCF, on the other hand, raise expectations that problems can be solved and that continuous effort and inquiry will result in success.

T-9: Self Regulation orients students to seek and use information to adjust their own learning process. This includes asking questions for clarification. As for all the KCF, this function is developed in response to mediation. Students who do not have this KCF do not solicit information to guide their learning process and fail to use even available information as feedback to regulate their learning. They repeat mistakes and continue to apply strategies after evidence suggests they should be abandoned. Non-intellective factors of knowledge construction may also play a role. For example a student may have little curiosity and need to find out how or why things happen (A-5) and therefore be less likely to ask questions.

Backmapping Example #4: Grade 8 - Language Arts

Standard: Follows oral directions and asks questions for clarification.

Grade 8 - Language Arts

Standard 14: Follows oral directions and asks questions for clarification.

- R-2: Attention

- R-6: Verbal Tools and Concepts (Reception)

- T-8: Evoking from Memory

- C-9: Self-Regulation

- A-5: Curiosity

In order to follow oral directions, students must attend to the incoming information without being distracted by external or internal sources of interference. This implicates the KCF of R-2: Attention. The brain registers large amounts of information at any moment, but we only attend to a tiny subset. Within limits, as is the case with all the KCF, we have the ability to regulate how we allocate our attention. We can choose to listen, and noises we until then ignored pop out from the background. We can choose to be on the lookout for visual details, as when a detective scrutinizes a video that captured a crime scene. The development of attention as a KCF equips learners with the ability to regulate attention as a matter of a conscious choice. Students learn the relationship between allocating attention and gathering information. In the absence of this function, students may drift and be easy pray for distractions and even small variations in motivation.

The development of verbal tools and concepts (R-6) equips students with an understanding of the need for such tools within any area of academic functioning. Once they have this KCF, students will anticipate that verbal tools and concepts will accompany any new task and subject area, and they will be on the lookout for them. Students will know that these devices for information processing must be acquired in one or more of a small number of ways: Either they mush be taught by the teacher, looked up in a dictionary, inferred by context or acquired from questioning. When a learner encounters words or concepts that are ambiguous or unknown, it is this KCF which orients the student to take appropriate steps to achieve the necessary clarification. In the absence of this function, students tend to skip over new words and concepts with the predictable impact on the quality of their knowledge construction and performance.

Except when brief instructions are heard and carried out, students need first to store oral directions in memory and, then, at some later point, evoke them as needed. Both T-6: Interiorization and T-7: Mental Representation are involved in storing information in memory. Here, however, our focus is not on the self-evident problem that information not stored in memory cannot be recalled. Our focus, rather, is on the retrieval of stored information.

We can distinguish between two types of memory: Associative and analytical. The associative type is experienced as largely involuntary. It generally dominates the experience of memory as images enter the mind seemingly on their own accord. Our interest is in the analytical type which is activated by a KCF that orients the learner to deliberately search memory in order to retrieve stored information (T-8: Evoking from Memory). Unlike associative memory, evoking from memory is the product of a volitional act. In the absence of this KCF, students manifest a passive attitude towards memory that enables even properly stored information to go unclaimed when needed. The relative unfamiliarity with this KCF makes educators prone to conclude that students don't know when they, in fact, don't remember.

Here is the standard once again: Follows oral directions and asks questions for clarification. Let's turn to the portion about asking questions for clarification. The wording 'for clarification' hints at the difference between those who ask questions to advance the process of knowledge construction versus those who ask questions to bypass it ("What's the answer?") Poorly developed knowledge construction functions are often associated with unrewarded effort and low expectations of success. In traditional classrooms students with poor KCF frequently want just to be done and move on ("Hey, man, can't you just give me the answer?") Well developed KCF, on the other hand, raise expectations that problems can be solved and that continuous effort and inquiry will result in success.

T-9: Self Regulation orients students to seek and use information to adjust their own learning process. This includes asking questions for clarification. As for all the KCF, this function is developed in response to mediation. Students who do not have this KCF do not solicit information to guide their learning process and fail to use even available information as feedback to regulate their learning. They repeat mistakes and continue to apply strategies after evidence suggests they should be abandoned. Non-intellective factors of knowledge construction may also play a role. For example a student may have little curiosity and need to find out how or why things happen (A-5) and therefore be less likely to ask questions.

Backmapping Example #4: Grade 8 - Language Arts

Standard: Follows oral directions and asks questions for clarification.

Backmapping Academic Standards: Example #5 PDF

Grade 6 - Math

Standard 17: Identifies effects of basic transformations on geometric shapes.

In the absence of these functions students cannot apply precise, analytical cognitive strategies. Without these strategies they have to rely either on random, probabilistic or trial-and-error approaches. The ability to manipulate the geometric shapes, if available, is not likely to be of use, as physical manipulation, too, requires support from the identified KCF to be successful. In their absence, physical manipulation consists of unsystematic attempts to produce the required transformation by luck or chance. Yet even if a correct solution is generated, the learner is often unable to discern its accuracy as evidenced by continued fingering of the shapes.

Contrary to this shallow, low level of performance, the presence of the three identified KCF enable the learner to apply cognitively-based rules to transform a given geometric shape from a known initial state. This permits the learner to generate and investigate hypotheses (T-11) and to use physical manipulation, if allowed, as a means of verifying solutions relative to specific, mentally anticipated outcomes.

Backmapping Example #5: Grade 6 - Math

Standard: Identifies effects of basic transformations on geometric shapes.

Grade 6 - Math

Standard 17: Identifies effects of basic transformations on geometric shapes.

- R-3: Spatial Orientation

- T-6: Interiorization

- T-7: Formation of Mental Representations

- T-12: Generation of Mental Transformations

In the absence of these functions students cannot apply precise, analytical cognitive strategies. Without these strategies they have to rely either on random, probabilistic or trial-and-error approaches. The ability to manipulate the geometric shapes, if available, is not likely to be of use, as physical manipulation, too, requires support from the identified KCF to be successful. In their absence, physical manipulation consists of unsystematic attempts to produce the required transformation by luck or chance. Yet even if a correct solution is generated, the learner is often unable to discern its accuracy as evidenced by continued fingering of the shapes.

Contrary to this shallow, low level of performance, the presence of the three identified KCF enable the learner to apply cognitively-based rules to transform a given geometric shape from a known initial state. This permits the learner to generate and investigate hypotheses (T-11) and to use physical manipulation, if allowed, as a means of verifying solutions relative to specific, mentally anticipated outcomes.

Backmapping Example #5: Grade 6 - Math

Standard: Identifies effects of basic transformations on geometric shapes.

Backmapping Academic Standards: Example #6 PDF

Grade 7 - Math

Standard 28: Compares and orders natural numbers, integers, fractions, decimals and percents.

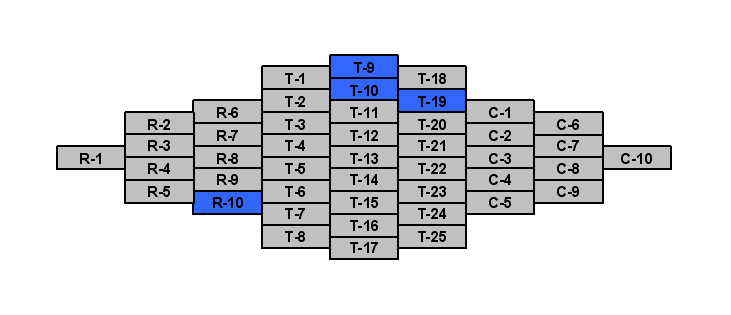

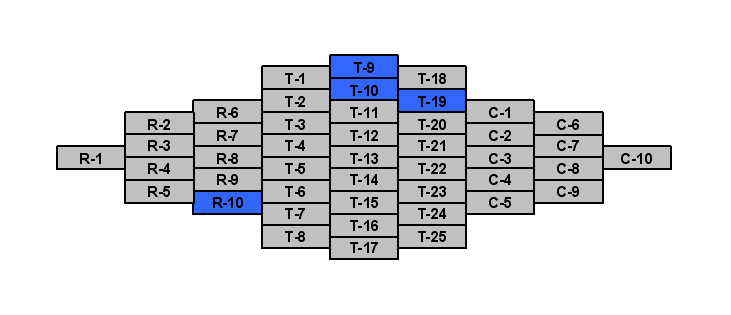

The performance of the mathematical operations (T-19) is supported by a series of prerequisite knowledge construction functions (KCF). These include simultaneous consideration of multiple sources of information (R-10), comparisons to identify similarities and differences (T-9), and ordering and grouping (T-10).

The development of R-10: Use of Multiple Sources of Information orients students to the difference between concurrent versus alternate or sequential consideration of sources of information. Concurrent or joint consideration of multiple sources of information is often required for problem solving and decision making (T-20). Keeping appointments requires joint consideration of space and time. Time and temperature must be considered concurrently when cooking a meal. Speed and distance must be considered together to decide how hard to apply the brakes. A decision to purchase a garment may require simultaneous consideration of size, color, fabric, design and price. For the purpose of achieving the present math standard, students need to give concurrent consideration to the signs or notation that are used to indicate fractions, decimals and percentages so they can use T-12: Mental Transformation to go back and forth between them. For example: 1/2 = .5 = 50%.

The KCF of comparative behavior (T-9) is needed to identify differences in magnitude between numbers (e.g. smaller than, larger than), and the KCF of ordering and grouping (T-10) is needed to sequence the identified magnitudes within the sets of natural numbers and integers.

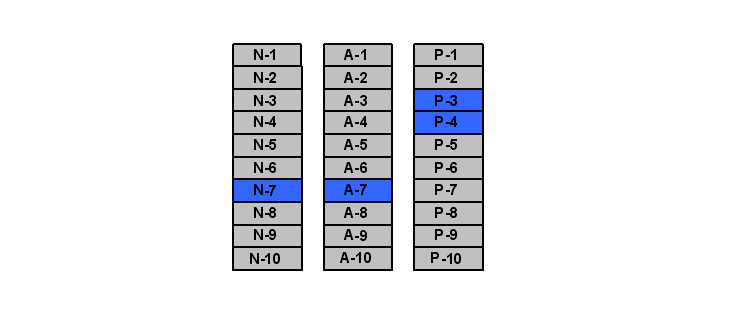

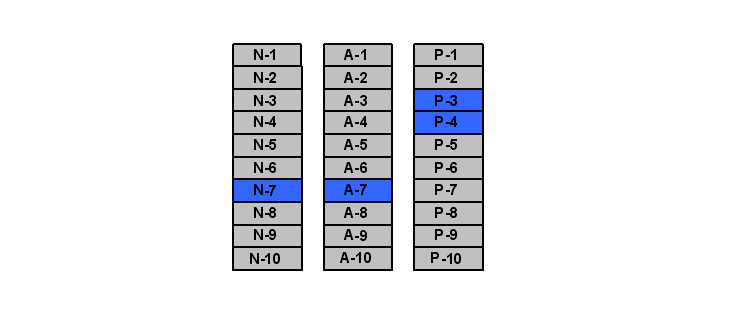

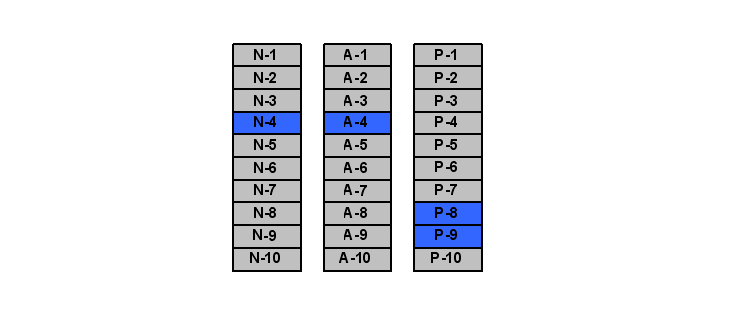

The contributions of non-intellective and performance KCF are as important to a student's overall academic results as the intellective KCF. Non-intellective and performance functions always play a role, and, sometimes, they stand out. For example, the ability to manage frustration (A-7) or invigorate a boring task by turning it into a challenge (N-7) are likely both to be a factor in the event students perceive a given math task on this standard to involve a positively endless sequence of numbers. The acquisition of proficiency through the development of efficient work routines (P-3) and effective habits (P-4) can, likewise, serve to increase a student's capacity to manage demanding or motivationally challenging tasks. - The graph showing the backmapped standard is provided below.

Backmapping Example #6: Grade 7 - Math

Standard: Compares and orders natural numbers, integers, fractions, decimals and percents.

Grade 7 - Math

Standard 28: Compares and orders natural numbers, integers, fractions, decimals and percents.

- R-10: Use of Multiple Sources of Information

- T-9: Comparative Behavior

- T-10: Ordering and Grouping

- T-19: Mathematical operations

- N-7: Need for Challenge

- A-7: Frustration Tolerance

- P-3: Automatization

- P-4: Habit Formation

The performance of the mathematical operations (T-19) is supported by a series of prerequisite knowledge construction functions (KCF). These include simultaneous consideration of multiple sources of information (R-10), comparisons to identify similarities and differences (T-9), and ordering and grouping (T-10).

The development of R-10: Use of Multiple Sources of Information orients students to the difference between concurrent versus alternate or sequential consideration of sources of information. Concurrent or joint consideration of multiple sources of information is often required for problem solving and decision making (T-20). Keeping appointments requires joint consideration of space and time. Time and temperature must be considered concurrently when cooking a meal. Speed and distance must be considered together to decide how hard to apply the brakes. A decision to purchase a garment may require simultaneous consideration of size, color, fabric, design and price. For the purpose of achieving the present math standard, students need to give concurrent consideration to the signs or notation that are used to indicate fractions, decimals and percentages so they can use T-12: Mental Transformation to go back and forth between them. For example: 1/2 = .5 = 50%.

The KCF of comparative behavior (T-9) is needed to identify differences in magnitude between numbers (e.g. smaller than, larger than), and the KCF of ordering and grouping (T-10) is needed to sequence the identified magnitudes within the sets of natural numbers and integers.

The contributions of non-intellective and performance KCF are as important to a student's overall academic results as the intellective KCF. Non-intellective and performance functions always play a role, and, sometimes, they stand out. For example, the ability to manage frustration (A-7) or invigorate a boring task by turning it into a challenge (N-7) are likely both to be a factor in the event students perceive a given math task on this standard to involve a positively endless sequence of numbers. The acquisition of proficiency through the development of efficient work routines (P-3) and effective habits (P-4) can, likewise, serve to increase a student's capacity to manage demanding or motivationally challenging tasks. - The graph showing the backmapped standard is provided below.

Backmapping Example #6: Grade 7 - Math

Standard: Compares and orders natural numbers, integers, fractions, decimals and percents.

Backmapping Academic Standards: Example #7 PDF

Grade 8 - Math

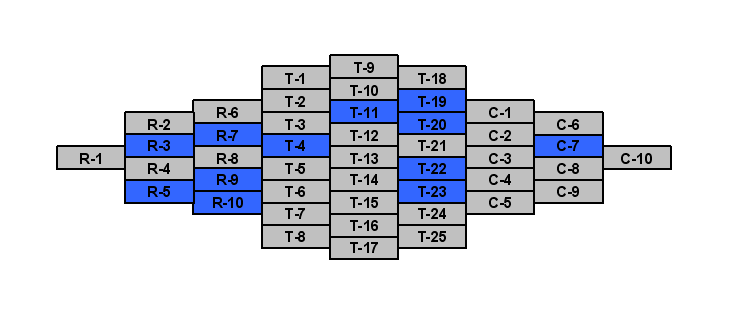

Standard #43: Collects and organizes data, determines appropriate method and scale to display data, and constructs frequency distributions; bar, line, and circle graphs; tables and charts; line plots, box and whisker plots, and scatter plots.

Remember, while an academic standard may be backmapped into a larger number of KCF, you and your students will most often focus on just a few functions within any given lesson devoted to the standard (see B-4: Instructional Delivery - Connecting Content and Process).

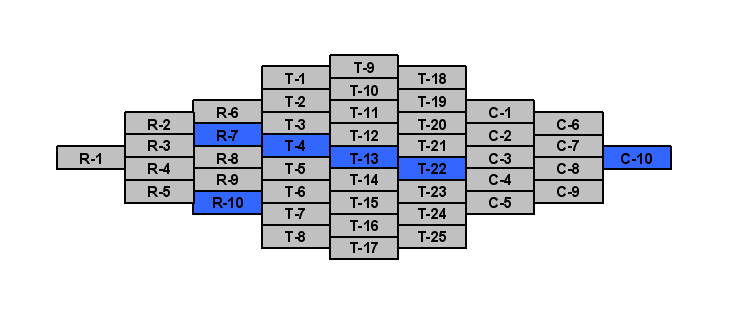

Backmapping Example #7: Grade 8 - Math

Standard: Collects and organizes data, determines appropriate method and scale to display data, and constructs frequency distributions; bar, line, and circle graphs; tables and charts; line plots, box and whisker plots, and scatter plots.

Grade 8 - Math

Standard #43: Collects and organizes data, determines appropriate method and scale to display data, and constructs frequency distributions; bar, line, and circle graphs; tables and charts; line plots, box and whisker plots, and scatter plots.

- R-3: Spatial Orientation

- R-5: Use of Symbols and Signs

- R-7: Systematic Exploratory Approach

- R-9: Need for Precision (Reception)

- R-10: Multiple Sources of Information

- T-4: Investment in the Receptive Process

- T-11: Hypothetical Thinking

- T-19: Mathematical Operations

- T-20: Decision-Making

- T-22: Goal Seeking and Goal Setting

- T-23: Planning

- C-7: Need for Precision (Communication)

Remember, while an academic standard may be backmapped into a larger number of KCF, you and your students will most often focus on just a few functions within any given lesson devoted to the standard (see B-4: Instructional Delivery - Connecting Content and Process).

Backmapping Example #7: Grade 8 - Math

Standard: Collects and organizes data, determines appropriate method and scale to display data, and constructs frequency distributions; bar, line, and circle graphs; tables and charts; line plots, box and whisker plots, and scatter plots.

Backmapping Academic Standards: Example #8 PDF

Grade 6 - Science

Standard #8: Describes how energy and work are related.

The development of the KCF of abstractions orients students to comprehend the particular in light of the general and to illustrate the general with the help of the particular. As students develop this function they practice moving back and forth between concrete situations and abstract rules. Holding a pencil and dropping it illustrates the abstract principle of gravitation. The abstract principle of photosynthesis explains the conversion of light energy into chemical energy which occurs in plants and other living organisms when sunlight transforms carbon dioxide and water into glucose and oxygen.

Prior to the development of T-13: Abstractions, students often miss opportunities to modify abstractness, whether up or down, as an aid to problem solving. Tasks that might be solved with the help of a general principle or a concrete example that could be procured may instead be botched or abandoned.

Backmapping Example #8: Grade 6 - Science

Standard: Describes how energy and work are related.

Grade 6 - Science

Standard #8: Describes how energy and work are related.

- T-13: Abstractions

- T-14: Establishing Relationships

- T-16: Strategies for Inferential Thinking

- C-5: Countering Egocentric Communication

- C-6: Verbal Tools and Concepts (Communication)

The development of the KCF of abstractions orients students to comprehend the particular in light of the general and to illustrate the general with the help of the particular. As students develop this function they practice moving back and forth between concrete situations and abstract rules. Holding a pencil and dropping it illustrates the abstract principle of gravitation. The abstract principle of photosynthesis explains the conversion of light energy into chemical energy which occurs in plants and other living organisms when sunlight transforms carbon dioxide and water into glucose and oxygen.

Prior to the development of T-13: Abstractions, students often miss opportunities to modify abstractness, whether up or down, as an aid to problem solving. Tasks that might be solved with the help of a general principle or a concrete example that could be procured may instead be botched or abandoned.

Backmapping Example #8: Grade 6 - Science

Standard: Describes how energy and work are related.

Backmapping Academic Standards: Example #9 PDF

Grade 7 - Science

Standard #4: Selects and uses multiple types of print and non-print sources for information on science concepts.

Note that a transformation function (T-4: Investment in Reception) guides the use of the reception function R-7: Systematic Exploratory Behavior. This is not an exception. The early T-functions (T-1: Stream of Consciousness, T-2: Experience of Disequilibrium, and T-3: Preliminary Problem Analysis) signify the onset of cognition and shape the early phase of the mental act. T-4: Investment in Reception relies on the results of the earlier T-functions to guide the use of the receptive KCF.

T-4: Investment in Reception provides support for the specific allocation of attention (R-2), for the mobilization of spatial (R-3) and temporal (R-4) orientation, for the clarification of traces, symbols and signs (R-5), for the clarification of verbal tools and concepts (R-6) and for guiding the application of systematic exploratory behavior (R-7).

T-4: Investment in Reception identifies the types of information initially seen to be relevant. Based on such information the learner may, for example, in a jigsaw puzzle, attend to shapes rather than colors. In a study of certain living organisms in a marine environment a student may ignore immobile entities and only look for something that stirs or moves. This KCF enables learners to use all their receptive KCF with reference to specific preliminary criteria as they pursue more definitive problem definitions.

Learners who do not have T-4: Investment in Reception do not capitalize even on preliminary problem analyses (T-3) they may have carried out. As a result, they apply their reception functions in a more haphazard manner which makes it more difficult to establish the accurate nature of a problem and collect information that is relevant to its solution.

Backmapping Example #9: Grade 7 - Science

Standard: Selects and uses multiple types of print and non-print sources for information on science concepts.

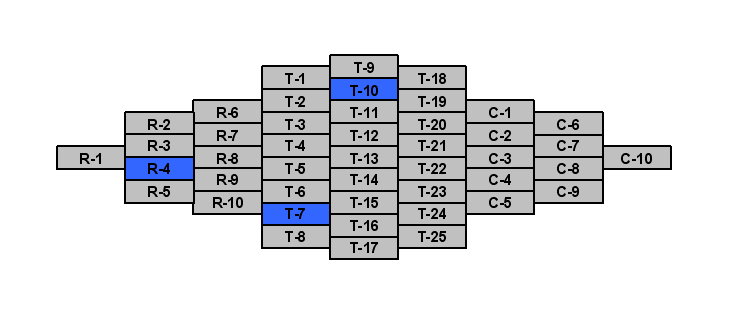

Grade 7 - Science

Standard #4: Selects and uses multiple types of print and non-print sources for information on science concepts.

- R-7: Systematic Exploratory Behavior

- R-10: Use of Multiple Sources of Information

- T-4: Investment in Reception

- T-13: Abstractions

- T-22: Goal Seeking and Goal Setting

- C-10: Self-Regulation and Autonomy

Note that a transformation function (T-4: Investment in Reception) guides the use of the reception function R-7: Systematic Exploratory Behavior. This is not an exception. The early T-functions (T-1: Stream of Consciousness, T-2: Experience of Disequilibrium, and T-3: Preliminary Problem Analysis) signify the onset of cognition and shape the early phase of the mental act. T-4: Investment in Reception relies on the results of the earlier T-functions to guide the use of the receptive KCF.

T-4: Investment in Reception provides support for the specific allocation of attention (R-2), for the mobilization of spatial (R-3) and temporal (R-4) orientation, for the clarification of traces, symbols and signs (R-5), for the clarification of verbal tools and concepts (R-6) and for guiding the application of systematic exploratory behavior (R-7).

T-4: Investment in Reception identifies the types of information initially seen to be relevant. Based on such information the learner may, for example, in a jigsaw puzzle, attend to shapes rather than colors. In a study of certain living organisms in a marine environment a student may ignore immobile entities and only look for something that stirs or moves. This KCF enables learners to use all their receptive KCF with reference to specific preliminary criteria as they pursue more definitive problem definitions.

Learners who do not have T-4: Investment in Reception do not capitalize even on preliminary problem analyses (T-3) they may have carried out. As a result, they apply their reception functions in a more haphazard manner which makes it more difficult to establish the accurate nature of a problem and collect information that is relevant to its solution.

Backmapping Example #9: Grade 7 - Science

Standard: Selects and uses multiple types of print and non-print sources for information on science concepts.

Backmapping Academic Standards: Example #10 PDF

Grade 8 - Science

Standard #11: Examines how land formations influence development of an area.

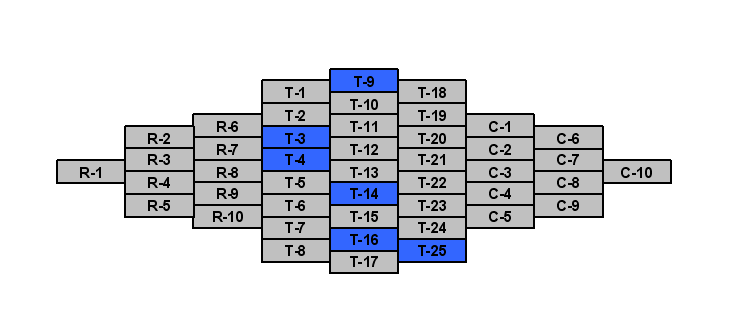

Backmapping Example #10: Grade 8 - Science

Standard: Examines how land formations influence development of an area.

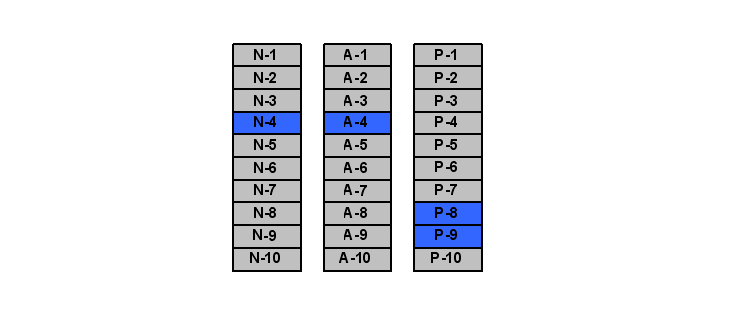

Grade 8 - Science

Standard #11: Examines how land formations influence development of an area.

- T-3: Preliminary Problem Analysis

- T-4: Investment in the Receptive Process

- T-9: Comparative Behavior

- T-14: Establishing Relationships

- T-16: Inferential Thinking

- T-25: Summative Thinking

- N-4: Complexity

- A-4: Explanatory Style

- P-8: Enthusiasm for Learning

- P-9: Insightful Reflection

Backmapping Example #10: Grade 8 - Science

Standard: Examines how land formations influence development of an area.